Smile! You Might Be on Camera:

The PDPA and Public Photography in Singapore

Written by:

Senior Consultant

Sapience Consulting

Imagine you are savouring your favourite nasi lemak at a bustling hawker centre. The famous nasi lemak stall opens only four mornings a week and typically sells out by 1 pm. While enjoying the delicious food, you notice the long queue of customers at the stall and feel grateful to have arrived slightly earlier, avoiding the crowd.

A well-known food blogger visits the stall and begins taking vibrant photos of the stall and the customers, including you in the background. However, you aren’t asked for permission. Is the food blogger required to seek consent from customers before taking their photos?

Today, an enormous number of photos and videos are captured quickly and easily with mobile phones in public spaces, often without our awareness that we are being photographed. How does the Personal Data Protection Act 2012 (PDPA) protect us, considering that facial images of identifiable individuals are considered personal data?

In this blog, let’s explore how the PDPA applies to photography in public spaces and learn about individuals’ rights regarding public photography.

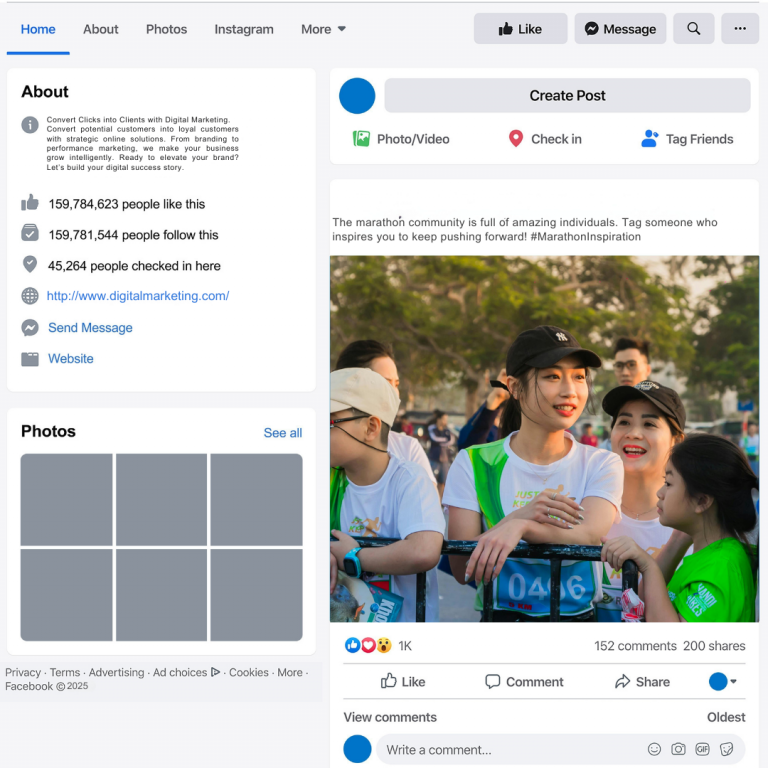

Story 1: The Marathon Snap

Jessica participates in a large city marathon in Singapore. While running, she notices photographers along the race route taking pictures of the runners. Later, she discovers that her photo has been posted on a digital marketing company’s Facebook page to promote their marketing campaigns.

According to the PDPA, such photos are considered personal data if they are taken at a location or event where the individual is present and that is open to the public. Generally, the PDPA does not apply to photos taken for personal purposes. However, when an organisation collects and uses photos for commercial purposes, such as marketing, the PDPA does apply. In this case, since the digital marketing company is using Jessica’s photo for commercial reasons, it is not in compliance with the PDPA because it did not obtain Jessica’s consent.

Takeaway – The PDPA protects individuals even in public places. Organisations must ensure that their use of photos aligns with PDPA obligations, especially when those images are used for marketing purposes.

Story 2: Caught in Class at a University

I recently attended a course at a public university in Singapore. After registering online as a visitor, I received a QR code that I was required to scan before entering a gated section of the building. This area contains several seminar and training rooms that are accessible to registered attendees, as well as university staff and students. During my visit, I noticed a group of students filming people and activities in this section as part of their student project.

I discussed with a few classmates whether consent was necessary for the video recording. Some believed that the gated area should not be considered public space because the gates restrict access to the general public. However, others argued that the area is open to the public since a significant number of university staff and students can easily access it.

Takeaway – The mere presence of some restrictions is not enough to classify a location as private. A place that is open to a large number of people and is easily accessible despite physical barriers can often still be regarded as a public space.

Story 3: The Influencer’s Park Vlog

Chloe, a social media influencer, is conducting a photoshoot for a sponsored post in a popular park in Singapore. She and her photographer are focused on capturing the perfect shots of her with the product. In several of their videos, other park visitors are inadvertently included in the background—jogging, picnicking, or simply passing by. Chloe shares these images and videos on her social media platforms, which boast a large following.

While incidental inclusion of individuals in public footage may not always require consent, the deliberate use of identifiable images for commercial purposes — such as Chloe’s vlog — triggers obligations under the PDPA. Organisations, including influencers acting as businesses, must either obtain consent or justify an exception. The question arises: Was the collection and use of these background individuals’ images reasonable and appropriate for promoting a product featuring Chloe, in accordance with the Purpose Limitation Obligation under the PDPA?

Takeaway – The PDPA applies to content creators who monetise identifiable personal data, even in public spaces. Individuals have the right to access their data and request corrections, such as anonymisation, if organisations do not comply.

Why the PDPA Matters in Public Photography

These stories illustrate that the PDPA isn’t just about databases or online forms — it extends to everyday scenarios like photography. Key takeaways include:

• Personal Data Definition – Photos that identify individuals are personal data under the PDPA.

• Consent and Notification – Organisations must inform individuals and obtain consent (or rely on exceptions) before using their images, especially commercially for a business purpose.

• Purpose Limitation Obligation – Personal Data can only be used for the purpose it was collected for.

Reflecting on the initial story, you likely now understand whether the food blogger needs to obtain consent from customers to take their photos.

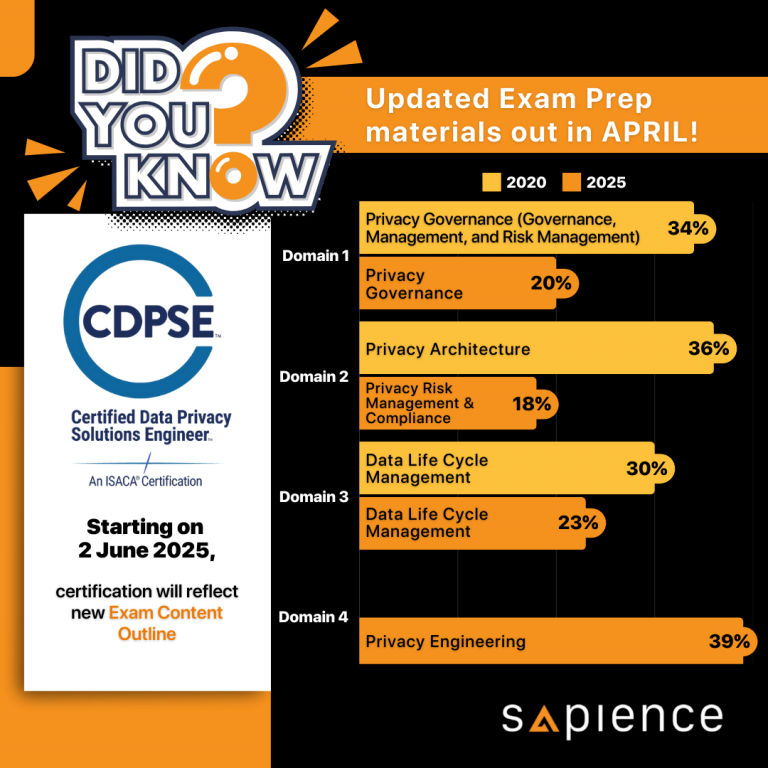

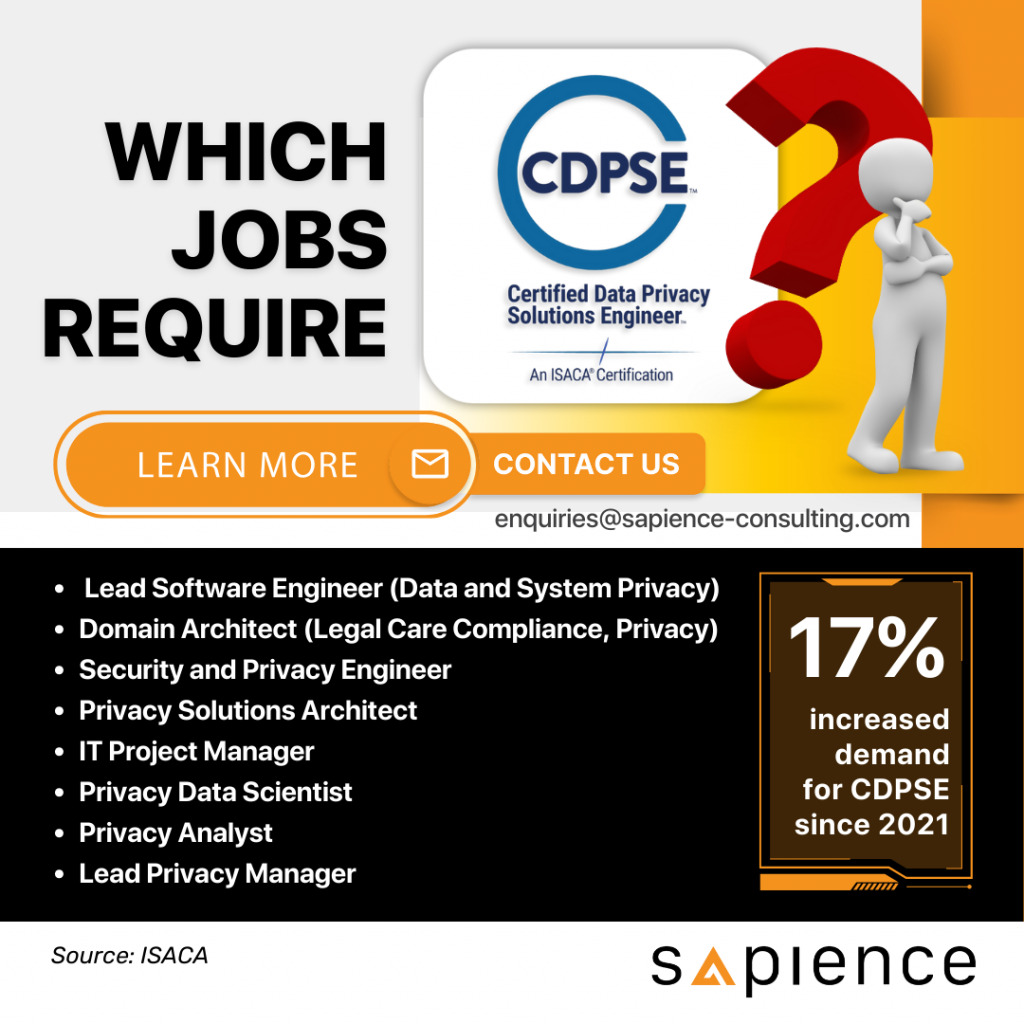

Understanding the PDPA’s implications for our increasingly digital world is no longer optional, but essential. As a trusted ISACA Accredited Training Partner, Sapience offers the globally recognised CDPSE certification, ensuring you receive expert-led instruction and up-to-date knowledge. By mastering the skills to implement effective privacy solutions, you can not only enhance your career prospects in a high-demand field but also contribute to safeguarding individual rights and fostering trust in the digital age. Take action now to become a vital part of the solution – With updated exam preparation materials for the June 2, 2025, changes, now is the ideal time to invest in your future. Discover the power of CDPSE with Sapience.

Check out our IBF and SSG funded courses! There is no better time to upskill than now!